Oaklands is a small town in the New South Wales Riverina district. It’s population today would be, I’m guessing, about 350, a few hundred less than it would have had in 1940. Kevin, my father, worked for Kevin, his uncle, in the Rourke Brothers stock and station agency business. Kevin Rourke was an excellent auctioneer and my father, his clerk.

Kevin enlisted in the Army on 5 Aug 1940. Sometimes I wonder whether his enlistment was simply a ruse to leave Oaklands. He had worked for his uncle since the age of 16 and was now almost 22. I think Kevin felt he was in a rut and just wanted to move on. He had been dating a local girl, Joan Dunstan, but their relationship wasn’t a serious enough to keep him in Oaklands. After completing basic training, Kevin was allocated to the Australian Army Service Corps as a truck driver in the 17th Brigade of the Sixth Division. As you'll be aware from previous blogs, Kevin got caught up in the evacuation of Greece, became a prisoner of war and was interned in Camp 10029/GW in Austria.

Joan corresponded with Kevin throughout his internment in Klagenfurt. In about 1943, she moved to Melbourne, fell in love and got married. This news wasn’t shared with Kevin, a decision made jointly by Joan and Kevin’s family. She continued to write to Kevin regularly.

Camp 10029/GW was in the Klagenfurt suburb of Waidmannsdorf, about 2 miles from both the CBD and the railway yards. By mid-1944, air raids had become a regular event in Klagenfurt. Under the terms of the Geneva Convention, anti-aircraft defenses were not permitted to be closer than 600 metres from a POW compound. This was precisely the distance between a gun pit containing a Bofors 40 mm ack-ack and Kevin’s camp.

About one kilometre from the camp there was a small hill covered by scrubby trees. Today's passers-by would see a few hectares of uncultivated scrub amidst an otherwise tidy light-industrial area. A closer look and some scrub-bashing would reveal a steel door covered in graffiti. In 1944, after Klagenfurt's first bombardment, a contractor using POWs and forced labourers from France, hollowed out the hill and constructed a bomb shelter. In the year that followed, it would be used by the local citizenry and sometimes by the POWs themselves.

The Bombing

For the POWs in Camp 10029/GW, Sunday the 18th of February 1945 began the same as any other. Most of the men had spent the morning working in the bitter cold and had returned to the camp at around 11 o'clock. There’s was a 6½-day work week. In the warmer months they would spend the afternoon playing sports or just resting but in February, typically the coldest month, they remained in their huts either huddled around the heater shooting the breeze, playing cards, or napping on their bed.

On that particular day, the air-raid sirens sounded about noon and the men were called on parade. About 300 men ran for the pits dug to shelter them from wayward bombs. But taking shelter wasn't compulsory. Kevin told me that some 40 men remained behind on that day, mostly because they were either fed up, depressed, or in the camp hospital. Some never believed that bombs would ever be dropped on the camp. No bombs had fallen on the camp in the past, but this time they did. In 2014, Australian journalist and television presenter, Barrie Cassidy, published a book called Private Bill. His father, Bill Cassidy, was also a POW in 10029/GW. Cassidy wrote:

Suddenly, a line of bombs tore open the ground along the fence line, near the camp’s front gates. Within seconds, more bombs landed and ripped through the barracks. As Bill dashed for the door, the giant stove in the centre of the room came crashing down, crushing a man beneath it – the prisoner let out a piercing squeal, then fell silent. Bill realised that nothing could be done for him and charged outside.

There was pandemonium throughout the camp as the full horror of the bombing hit home. Bill joined the group of men milling around a trench that he had been dug right outside the camp hospital. He learned that a bomb had blown out the sides of the trench, causing it to collapse on three patients. Just as he registered that that two men were wailing in pain and panic, he remembered that Alan Eason had been admitted to the hospital the day before. Then Bill heard Alan’s voice, calm and measured, informing his would-be rescuers from the bottom of the trench that he had been ‘badly knocked about.’ Alan could just be seen through the gap in the rubble. While the men dug feverishly, he asked for cigarettes to be passed down to him - he said he would be all right if they kept the smokes coming. Two hours later, the men were freed. Two of them survived, but Alan died from his injuries the following morning.

Six POWs, three Australians and three British, were killed. It was thought that a bomber was attempting to bomb the ack-ack gun but somehow the bombs did not release as intended, were jettisoned, and inadvertently fell on the camp.

When Kevin arrived home, he was told that Joan had married and was living in the Melbourne. A few months later, he received this letter from Joan.

Newsagency,

162 Bridge Road

Richmond, Victoria

Sunday, 30th

Dear Kevin,

First of all, I must tell you how glad I was to hear you are home and well after such a long time. Mary Cameron told me all about your “Welcome Home.” It must have been all very bewildering for you.

I am writing to you at the request of one of our customers. We have a photo framing agency here and one day a lady brought a photo into me to be framed. I noticed that the photo was of POWs and she told me it was taken at Stalag 18A and showed me her son in the group. When I was putting the photo away I noticed someone very familiar and it was you looking very fit and well.

I told her (about this) when she came back with the photo and she then told me her son Jeff never made it home, that he died whilst in Stalag. She asked me if I had your address and if so, could I write to you and find out something about her late son. His name was Jefferson Gilbert. I hope you don’t mind but I think she would just like to know whether or not you knew him, et cetera.

Six men were killed in the Sunday bomb raid. Jeff Gilbert was one of them. Kevin knew Jeff well. They were hut-mates and on occasions they were photographed together. Jeff was one of those who made the decision not to go to the bomb shelter. Kevin told me that Jeff refused to move from his bed as an act of defiance.

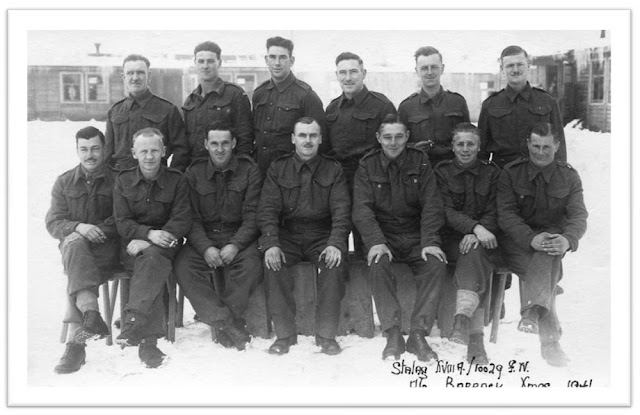

Kevin is first on the left in the back row. Jeff Gilbert is fourth from the left in the same row.

On duty in the cookhouse. Jeff Gilbert id in the foreground, Kevin id in the very background.

The Australian Tug O'War team photo taken on the annual 'Empire Games' sports day. Bill Cassidy is seated first left and Alan Eason, a champion school boy rugby player from Sydney, sits in the middle with a towel around his neck.